Head study of Turk the Dogue de Bordeaux at Tring.

The Right Stuff

I’ve learned through hard experience that there are basically two reactions to the mention of taxidermied dogs: One is “That’s disgusting.” The other is “That’s fascinating.”

If you count yourself among the former, you’d be advised to stop reading now.

The British dogapalooza known as Crufts is of course all about canines with pulses. But on my first visit to this bucket-list show earlier this month (“A Crufts virgin!” exclaimed more than one friend when I saw them on the other side of the pond), a trio of friends and I set off to view a collection of taxidermied purebred dogs improbably nestled in the Hertfordshire countryside. And what we found there was fascinating – especially if you are a Molosser lover.

The onomatopoeically named village of Tring – can you hear an old rotary-phone chirpily b-ringggging when you say it aloud? – is about an hour and a half southeast of the bustling show held at National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham. As Toy and Utility (what we call Non-Sporting) dogs were streaming toward the NEC’s cavernous exhibition halls, we were motoring along the bucolic byways, struggling to override the urge to veer to the right lane and craning our necks to glimpse the newborn lambs in the fields.

Tring has two claims to fame: It was the birthplace of George Washington’s grandfather, who left for Virginia and never came back; and it is the home of a world-famous museum of animal taxidermy.

Our destination, the Natural History Museum at Tring, was once the private museum of Lionel Walter Rothschild. (Yes, of those Rothschilds.) As eccentric as he was disinterested in the family banking business, the budding baron declared at the tender age of seven that he would grow up to “make a museum.” It was no idle threat: Within a couple of years he had amassed an impressive collection of beetles, butterflies, birds, fish and mammals. To add to his zoological obsession, a mob of kangaroos hopped languidly around the estate grounds, and later Rothschild famously maintained a stable of zebras that he put in harness to draw his carriage all the way to Buckingham Palace.

Rothschild driving a team of zebras: Conventionality wasn't his strong suit.

When Rothschild turned 21, his parents gifted him with the funding and land for his longed-for museum, and a handful of years later, in 1892, he opened the doors to what became the largest zoological collection ever assembled by one person.

At the time, a Victorian visitor to the charming brick building marveled at its contents, from “a bulky Indian sawfish of unpardonable length” to a “big brute” of a white rhinoceros. At its peak, Rothschild’s collection included 300,000 bird skins, 200,000 bird eggs, 2,250,000 butterflies and 30,000 beetles, as well as thousands of mammals, reptiles, and fishes.

But no dogs.

Having no connection to Rothschild but for their residence in his museum, Tring’s collection of 88 taxidermied purebred dogs was assembled piecemeal at the Natural History Museum in London. After World War II, the preserved canines were sent to Tring, where they reside in its furthest corner and final gallery, number six, across from towering glass display cases of snakes and amphibians.

The dog gallery at Tring. Sighthounds are displayed first, followed by Working and Sporting dogs, including Molossers.

I suppose floor-to-ceiling cases of stuffed purebred dogs are a bit macabre. (At least that’s what the Facebook comments revealed when we posted our selfies taken in front of motionless Mastiffs and stationery Salukis.) But for serious students of purebred dogs, any ick factor is soon overtaken by awe for what lessons these frozen-in-time dogs have to teach us, particularly in terms of how much some of them have evolved in the intervening century.

Taxidermied Ibizan-hound head at Tring.

Taxidermied Ibizan-hound head at Tring.

The first dogs one encounters at the far end of this long glass gallery are the Sighthounds, ancient breeds and landraces that are the antitheses of the Molossers. There were three racing greyhounds that spanned a century of breeding; a Saluki and Afghan that, but for a bit of coat, were almost interchangeable, and a mounted Ibizan Hound head that reminded of the taxidermied elf heads in 12 Grimmauld Place from “Harry Potter” – big ears, you know.

But a few paces down the aisle was our first Molosser, a brindle Mastiff presented in 1922 by W.K. Taunton, a well-known Mastiff breeder of the time. This unnamed male was accompanied by Kathleen of Riverside, also a prize-winning brindle whelped in 1894, who unfortunately is not on display. Taunton, if you hadn't guessed it by now, was known for his brindles, and in fact Illustrated Kennel News in 1902 noted that "it was mainly due to his exertions that the brindle has been preserved, as fifteen or twenty years ago there was a great risk of it dying out, it not being at that time by any means a popular color."

The male on display at Tring was fascinating for his absolute exercise in restraint – there was only the slightest undulation of wrinkle on his head, and his relatively lithe body suggested a possible contribution from the likes of the houndy Great Dane standing beside him. That’s not to say mass wasn’t in vogue at the time: The nearby Saint Bernard — another unknown who has been on display at one museum or another since the 1803s — is dripping in skin and wrinkle, with pronounced haws.

This brindle Mastiff from the early 20th-Century is worlds away from his modern-day mates in terms of mass and wrinkle.

This strapping Mastiff certainly had the height and breadth of skull that telegraphed the breed development to come. But, like all the Molossers in this display, this early-20th-Century fellow was decidedly undercooked compared to our modern dogs. I’ll leave it to you to decide whether that’s a good thing – how much is too much.

Tibetan Mastiff at Tring.

Tibetan Mastiff at Tring.

The same applied to the museum's Tibetan Mastiff. Nearby, and quite a famous one at that: In the early 20th Century, this male was brought from Nepal for King George V, who then gave him to the London Zoo. Though he doesn’t have a great deal of size by modern standards, his headpiece is comparatively heavy and impressive: There is no doubt he would dissuade even the most foolhardy of intruders.

When I contacted breed expert Richard Eichhorn of Drakyi Tibetan Mastiffs, he was well aware of the Tring specimen of his breed.

“The dog on display at the Natural History Museum was typical of his time, and a representative of the mountain/flock type,” he replied. Though the dog is “correct in proportion, pigmentation, coat and overall breed type,” he was, at 58 centimeters (barely 23 inches), below the minimum height required of the breed today – he would be disqualified under the AKC standard, which stipulates males must be 25 inches or taller. “Still,” Eichhorn concludes, “he appears to be a dog that could do the job he was intended to do.”

One of the gnawing concerns at Tring is how much the taxidermist’s skill – or lack thereof – has changed the appearance of the dog before us. How accurate is the head, the substance, the overall impression of these dogs?

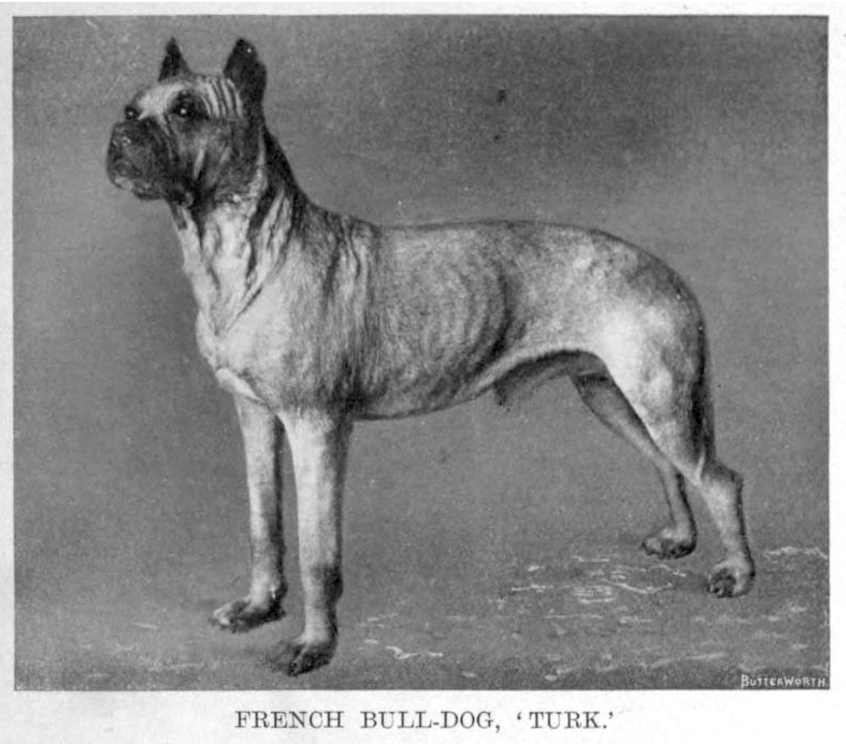

In the case of Turk the Dogue de Bordeaux, quite accurate indeed, though you’d be forgiven if you didn’t recognize him as a member of his tribe before reading the museum label. Turk was whelped in 1894 in Britain from two imported and accomplished French parents: His dam reportedly won a silver medal at the Paris dog show, and his sire was a celebrated fighting dog who batted his first bear at nine months old. This intriguing dog has unexpectedly cropped ears, a light fawn coat and a frame that does not have the depth of body that is so important for this breed. The fact that he is posed with two Bulldogs in the foreground only serves to underscore this even more.

For many, British-born Turk is not immediately identifiable as a Dogue de Bordeaux. Posed in front of him are 19th Century bulldogs.

For many, British-born Turk is not immediately identifiable as a Dogue de Bordeaux. Posed in front of him are 19th Century bulldogs.

But compared to a photograph taken of Turk in life, this taxidermied version is an honest approximation of who he was, though in perpetuity his painfully visible ribs have been plumped up, presumably with straw instead of fat. Turk is a reminder that in its infancy, the Dogue de Bordeaux had three regional types, with the Bordeaux type winning out in the end. Still, we can see important facets of breed type emerging: the well-developed brow, the beginnings of an upsweep to the chin and the resultant undershot jaw, nascent wrinkling on the muzzle and temples, the emerging dewlap, and the slight curve to the topline.

An image of Turk the Dogue taken in real life -- emphasis on the word "life."

Modern-day Victorian Bulldog, posed next to a decidedly older Old English Sheepdog.

Modern-day Victorian Bulldog, posed next to a decidedly older Old English Sheepdog.

Tring is home to a handful of modern dogs, too. One is Spike, a Victorian Bulldog whelped in 1992. Despite its name, the Victorian Bulldog is a modern breed, created by the late Kenneth Mollett to approximate a more active Bulldog type, abetted with the addition of Bull Terrier, Staffordshire Terrier and Bullmastiff blood.

Short or tall, bandy legged or lithe, spotted or brindled, lap warmer or guard dog, all of the dogs in the Tring gallery bespeak the very human impulses to categorize, to tinker, to improve and to evolve. The pleasure we get in seeing what they once looked like derives from our knowledge of where they are today. Our breeds can’t stay static any more than we can. It’s like that famous Woody Allen line from “Annie Hall” that compares a relationship to a shark: “It has to constantly move forward or it dies. And I think what we got on our hands is a dead shark.”

However much changed, the vast majority of the breeds at Tring – including, happily, all of its Molossers – have continued to tread water alongside us, dozens upon dozens of generations later.